When you hear talk about the “war on Christmas” it is worth remembering that the holiday we know as Christmas evolved from many different sources – mostly non-Christian. The Christian hierarchy in the early days of the church claimed December 25th as the birth date of Jesus with little or no evidence in the Bible to back up the claim but it did conveniently co-opt the various seasonal celebrations taking place. However, the wildness of the celebrations never ceased and the Puritans, first in England and later in New England, outlawed it.

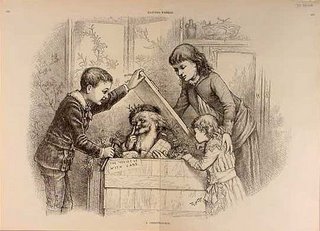

When you hear talk about the “war on Christmas” it is worth remembering that the holiday we know as Christmas evolved from many different sources – mostly non-Christian. The Christian hierarchy in the early days of the church claimed December 25th as the birth date of Jesus with little or no evidence in the Bible to back up the claim but it did conveniently co-opt the various seasonal celebrations taking place. However, the wildness of the celebrations never ceased and the Puritans, first in England and later in New England, outlawed it.The holiday festivities crept back into communities but it is important to note that Christmas at that time was nothing remotely similar to what we think of Christmas today. It was celebrated in the streets with a lot of drinking. Bands of the poor would demand entry into the homes of the well-to-do and demand food and drink -- "we want some figgy puddying". Encounters sometimes became violent and, with urbanization, potentially revolutionary. It was a reform movement in the early nineteenth century to bring Christmas into the home and instead of giving to the poor off the streets, giving was shifted towards the children of the household.

I recommend a very good book, The Battle for Christmas

Christmas seems to bring out the worst in America’s culture warriors. The Christian right continues its crusade against those waging “war against Christmas.” Multiculturalists have nearly banished “Merry Christmas” and “Silent Night” from the public domain and are now going after outdoor Christmas trees. Atheist activists like Sam Harris are goaded into defending the outing of their Christmas trees with the argument that it’s all secular anyway.

Harris is only partly right. The whole truth about Christmas is far more interesting and reveals why all can enjoy it. It is the perfect example of America’s mainstream process, a national rite that dissolves the boundaries between sacred and secular, pagan and civilized, insiders and outsiders.From the very beginning Christians have always had a tenuous hold on the holiday. The tradition of celebrating Jesus’ birth on the 25th of December was invented in the fourth century in a proselytical move by the Church Fathers that was almost too clever. The pre-Christian winter solstice celebrations of the rebirth of the sun, especially the Roman Saturnalia and Iranian Mithraic festivals, were recast as the Christian doctrine of the re-birth of the Son of God. Like many such syntheses, it is often not clear who was culturally appropriating whom. Certainly, throughout the Middle Ages, Christmas festivities like the 12 days of saturnalian debauchery, the veneration of the holly and mistletoe, and the Feast of Fools were all continuities from pagan Europe.

For this reason, the Puritans abolished Christmas. As late as the 1860s, Christmas was still a regular work and school day in Massachusetts. By then, however, its reconstruction was well on the way in the rest of the nation. America drew on the many variants of Christmas brought over by immigrants. It is telling that, in the making of Santa Claus, it is the English Father Christmas, derived from the pagan Lord of Misrule, rather than the more Christian Dutch St. Nicholas that dominates.

The commercialization of the holiday began as early as the 1820s, and by the last quarter of the 19th century a thoroughly unique American complex had emerged — ornaments, Christmas trees and the wrapping of gift boxes. Christmas further evolved in the 20th century with department store displays, Santas and parades, the outdoor Christmas tree spectacle, postage cards and secular Christmas songs. All American ethnic groups contributed to this national ritual.

The re-Christianization of the holiday emerged in tandem with its commercialization during the 19th century. Secularists did not distort or steal Christmas from Christians: in America they made it together. What’s more, as the cultural historian Karal Marling shows, the festival’s most compassionate aspect, charity, came mainly from the influence of Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol,” which, however, drew heavily on the largely invented accounts of a romanticized Merrie Olde England by the American travel writer Washington Irving.

The outcome of all this is a uniquely American national festival perfectly attuned to the demotic pulse of the common culture: its openness and vitality, its transcending appropriation of eclectic sources, its seductive materialism. It is, further, a mainstream process that dovetails exquisitely with more local expressions of America like Hanukkah and Kwanzaa, the former a reinvention of a minor Jewish rite, the latter a pure invention, in a manner similar to the wholly fictitious Scottish highland tradition that pipes up around the New Year. Kwanzaa borrowed heavily from Hanukkah, right down to the menorah, in fashioning the American art of mirroring the mainstream while doing one’s own ethnic thing. Decorating public Christmas trees with menorahs should be a soothing natural development in this glorious hall of cultural mirrors.

Ejecting Christmas from the public domain makes little sense, and not simply because religion only partly contributed to its emergence as a national rite. It should be possible to enjoy Christmas while recognizing its muted Christian element, even though one is neither religious nor Christian, in much the same way one might enjoy the glories of a Botticelli or Fra Angelico in spite of the unrelenting Christian presence in their art. In much the same way, indeed, that one might enjoy jazz, another gift of the mainstream, without much caring for black culture; or the American English language that unites us, in spite of Anglo-Saxon roots that are as deep as those of Father Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment